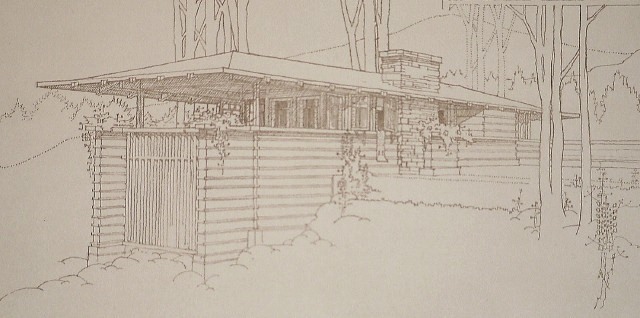

Myers temporarily took over an abandoned miner’s cabin and set to building a field office and permanent home using a catalog-ordered “house kit.” He supplemented native logs and scrounged barbed wire from a nearby abandoned sawmill to reinforce the daubing. This kept the house snug in cold weather. The station’s simple square shape and use of recycled materials reflect the Forest Service conservation ethic. A log barn and corrals accommodated the horses and livestock needed for the ranger’s self-sufficiency.

|

When Forest Service preservationists began extensive restoration, carpenters made wonderful discoveries. They found a teaching tool, forgotten beneath a layer of sheetrock, in young Robert’s upstairs bedroom. A historic timeline Emily drew on the wallpaper depicts the Stone Age and ancient Mediterranean history. Ranger Myers recycled everything. The house kit’s shipping crate framed the living and dining room doorway; wallpaper samples and opened mail filled in gaps around the windows and doors.

Today, visitors trade electricity and running water for a rare opportunity to live as the Myers family did a century ago. The station has an ambiance where the past and its energy linger. Remember this ghostly experience at the cabin?

The Judith River Ranger Station sleeps eight and is available for rental throughout the year. The station is equipped with propane heat, cook stove, and an adjacent modern vault toilet. For further information or to reserve the cabin, visit recreation.gov.