While John Owen was under the care of the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth at Helena, he had the opportunity to prove his title to the Fort Owen properties, but he was too ill. So his fort was auctioned at sheriff’s sale. Friends, wanting to believe he would recover, elected him to the 1873 territorial legislature. Owen could not attend.

|

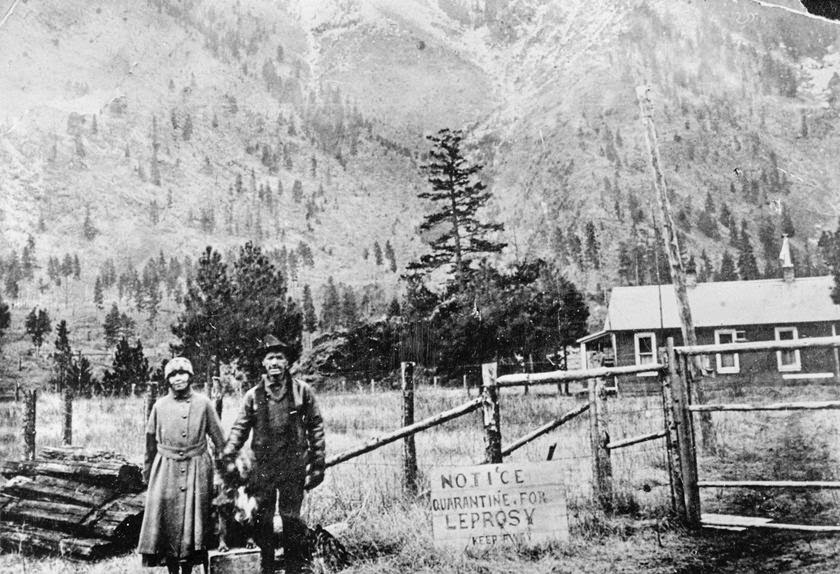

Major John Owen as he appeared in 1871.

Portrait from Dunbar and Philips, Journals and Letters of Major John Owen. |

For the next several years, Owen, indigent and incompetent, was shuffled back and forth between the sisters’ care and the Lewis and Clark County Hospital. At the end of January, 1877, during the Tenth Session of the Territorial Legislature, House Bill No.1, “an Act to establish and maintain a hospital for the insane, and otherwise provide for the insane of the Territory,” unanimously passed. Governor Potts approved the bill on February 16, 1877, the very day that the legislature adjourned. The bill contained the following clause: “...whenever, in judgment of the governor, it is desirable to send such insane person to friends out of the territory, he may do so at the expense of the territory . . . .” This clause was for Major Owen’s benefit and brought his days in Montana to an end.

The following morning, February 17, Tenth Legislative Assembly President W. E. Bass, Owen’s longtime close friend, escorted him from the territory. After an arduous journey by stage and rail, Bass handed over Major Owen to relatives in Philadelphia. Weeks later, on April 1, thirteen indigent mentally incompetent patients were admitted to the new, privately owned hospital at Warm Springs established under House Bill No. 1.

John Owen lived another twelve years, probably a victim of what we now know as Alzheimer’s disease. He died in 1889. The

Helena Weekly Herald of July 12, 1889, quietly noted John Owen’s passing: “. . . Maj. Owen was for a long time one of the most enterprising, prosperous, influential and public-spirited men in this section of the country. . . . In his prime he was a man of ability, culture and influence . . . . The older generation of Montanians will cherish pleasant memories of Maj. Owen as they first knew him.”

|

| Fort Owen today is a state monument, operated as a state park. |