In 1991, the American Institute of Architects honored Frank Lloyd Wright as the Greatest American Architect of All Time. His theory of organic architecture held that structures should be in harmony with humanity and the human environment. When he died in 1959, he had designed over five hundred homes and structures in thirty-six states and Japan, Canada, and England. Some four hundred remain today. Montana claims several examples of his work, including one project from 1908 when Wright’s career was just beginning to take off and another dating to the very end of his long architectural practice. The Como Orchards Colony, also known as the University Heights subdivision, in the Bitterroot Valley near Darby was an experimental planned community. Wright came to Montana in 1908 to research the site and designed the Como Orchards as a summer refuge for university professors.

A lodge and thirteen cottages were completed. One small cottage, a one-room cabin, and a tree-lined drive are all that remain today of Wright’s experiment. It was an innovative idea and a very early use of the prairie style that made Wright famous.

He also designed the Bitterroot Inn at Stevensville, but it burned to the ground in the 1920s. The Lockridge Medical Clinic in Whitefish, built in

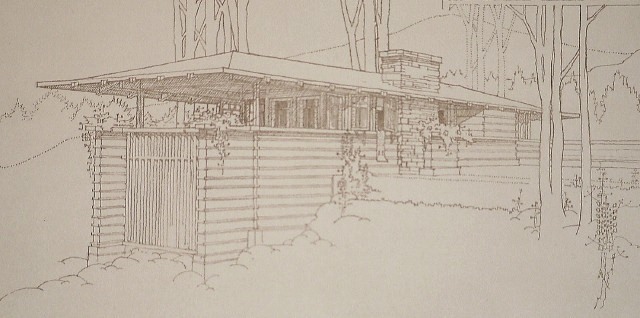

1961 1959, was one of Wright’s last designs. Dr. T. L. Lockridge insisted on the building’s construction even though his partners did not think it suitable as a medical clinic. For one thing, its hallways were too narrow for wheelchair access. When Lockridge died in

1964 1963, his two partners moved elsewhere, and Mrs. Lockridge sold the building. Now a law office, it is a surprising landmark in the middle of downtown Whitefish.

|

| The Lockridge Medical Clinic in Whitefish |

Update: Thanks to Ann Lockridge Christman for correcting the dates in the last paragraph.