2014 has been the year of both territorial Montana’s and Helena’s 150th anniversaries. The New Year brings yet another 150th milestone celebration: the birthday of the Montana Historical Society. The organization is the second oldest such organization west of the Mississippi, founded when a group of prominent and farsighted men gathered early in 1865 at the Dance and Stuart Store in Virginia City. They included pioneer brothers

James and Granville Stuart; vigilante prosecutor

Wilbur Fisk Sanders; Territorial Chief Justice Hezekiah Hosmer; territorial legislator F. M. Thompson; and mapmaker Walter DeLacy. Territorial Governor Sidney Edgerton signed the incorporation on February 2, 1865. Unlike most other historical societies, the Montana Historical Society was born while historic events were occurring, and not created as a nostalgic look backwards. Its initial purpose was “to collect and arrange facts in regard to the early history” of the territory. It does that and much, much more.

|

The Montana Historical Society was founded in the Dance and Stuart Store, Virginia City, in 1865.

Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives |

In 1873, the society moved its collection of first-run territorial newspapers and other documents to Helena. Soon after, on January 9, 1874, fire destroyed most of it when Wilbur Fisk Sanders’ law office burned. In 1887, rented quarters in the new territorial capitol at the

Lewis and Clark County Courthouse became a more permanent home. Reorganized in 1891, the society became a state agency. In 1902, it moved into its second home in the basement of the new Montana State Capitol. Reorganized again in 1949, the Veterans and Pioneers Memorial Building became the society’s current home in 1953. Collections of all kinds fill its galleries, its library, its and storage facilities.

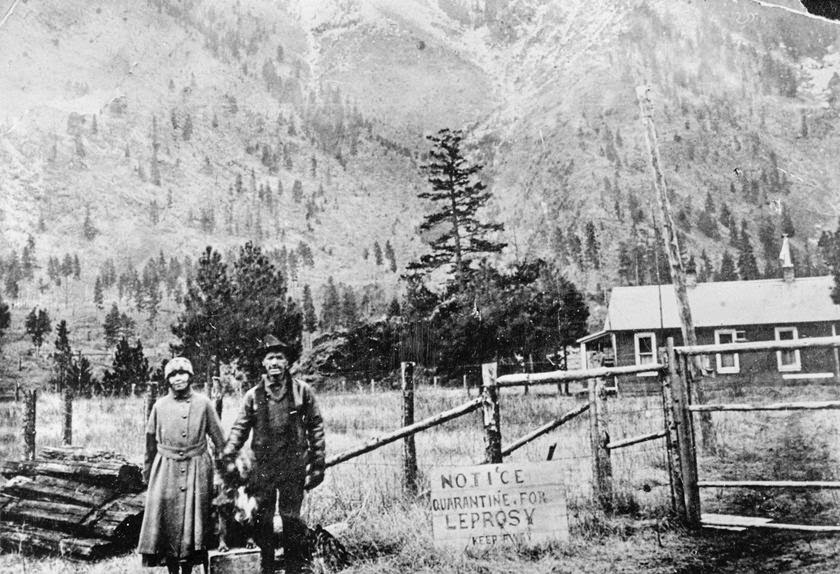

Today the society’s six programs are committed to education, research, and preservation that reach across the state in many ways. The research center includes 95 percent of all newspapers published in Montana; 18,000 reels of microfilm; 14,000 maps; 32,000 books and pamphlets; and 350,000 photographic images. The museum houses over 48,000 artifacts as well as textiles and extensive art collections. And the building is bursting at the seams.

The Montana Historical Society is the steward of our stories and belongs to all of Montana. On its 150th anniversary year, we invite you to visit us,

become a member, and support your history.