|

| Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, PAc 78-57 |

Wednesday, July 31, 2013

Montana State Prison’s Most Unusual Inmate

Paul Eitner was perhaps the Montana State Prison’s most colorful character. He was a German immigrant who worked as a porter at a Miles City saloon and lived in a local boarding house. One evening in January 1918, Eitner picked up his .38 revolver, strode down the hall and fired three times at a fellow lodger. The man died three days later. Eitner’s motive was never clear. At the last moment in court, he changed his plea from self-defense to guilty, hoping for leniency. The judge was not sympathetic and gave him a life sentence. Eitner was assigned to the state sanitarium at Galen to look after the prison’s flock of turkeys. He was thus employed until 1932 when he sold the all the birds to a passing farmer for twenty-five cents each. This incident earned him the nickname “Turkey Pete.” Eitner believed he had diamond mines and an imaginary fortune. Inmates printed “Eitner Enterprises” on checks in the prison shop, and he gave away millions of pretend dollars. He was mascot to the prison band and acted as manager of the boxing team, shadow boxing his way through every match. The prison board denied him parole a number of times believing Eitner could not adjust to the outside. In his later years, his prominent nose seemed to grow longer. Its extreme length made lighting his cigarettes potentially dangerous.

Paul “Turkey Pete” Eitner died in 1967 at the age of eighty-nine after serving forty-nine years in the state prison. Many mourned his passing and attended his funeral in the prison theatre, the only funeral ever held within the prison walls. His empty cell, #1 in the 1912 cell house, was never reassigned.

Monday, July 29, 2013

Thomas Dimsdale’s School

Health was among the many reasons that people came west to the booming gold camps. They believed that the high mountain climate could cure tuberculosis, but they did not realize that primitive living conditions and brutal winters could neutralize healthful benefits. Thomas Dimsdale was one of those pioneers afflicted with tuberculosis who came west for the mountain climate. He opened a private school in the winter of 1863-1864. Students paid two dollars a week to attend classes in this tiny cabin, which stood on Cover Street in Virginia City.

Later, as editor of the territory’s first newspaper, the Montana Post, Dimsdale wrote an account of the vigilantes in installments for the newspaper. It became Montana’s first published book, The Vigilantes of Montana, and is still in print. Mary Ronan was a student of Dimsdale's, and she later recalled in Girl from the Gulches, “Professor Dimsdale was an Englishman, small, delicate looking, and gentle. I liked him. It seemed to me that he knew everything. In his school all was harmonious and pleasant. While his few pupils buzzed and whispered over their assignments, the professor sat at a makeshift desk writing, writing, always writing. When, during 1864, The Vigilantes of Montana was being published at the Montana Post, I thought it must have been the composition of those articles that had so engrossed him. We children took advantage of Professor Dimsdale’s preoccupation and would frequently ask to be excused. We would run down the slope into a corral at the bottom of Daylight Gulch. We would spend a few thrillful moments sliding down the straw stacks.” Dimsdale was appointed the first territorial superintendent of schools in 1866, but he died soon after from the tuberculosis that brought him west. The tiny cabin, in ruins in a Virginia City back yard, was moved out of harm’s way to Nevada City in 1976.

|

| Thomas Dimsdale. Courtesy Yanoun.org |

|

| The Dimsdale School in its present location in Nevada City |

Labels:

books,

Girl from the Gulches,

medical history,

Nevada City,

schools,

Virginia City

Friday, July 26, 2013

Friday Photo: Sperry Chalet

|

| Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, PAc 93-25 A3 199 |

P.S. Remember this beautiful view in the Park?

Wednesday, July 24, 2013

Neihart, Montana

Neihart lies at the bottom of a densely timbered canyon along winding Highway 89. The tiny town traces its roots to 1881 when James Neihart and company discovered rich silver veins. By 1882, a crude wagon road connected it with White Sulfur Springs, and miners packed out the silver ore on horseback for processing at the Clendennin smelter twenty miles away. When the smelter shut down in 1883, ox-drawn freight wagons carried Neihart’s ore to Fort Benton where steamboats took it to distant ports. Even though the area was one of Montana’s richest, lack of transportation hindered development. In 1891, a spur of the Montana Central Railroad linked Neihart with the outside world. The new smelter at Great Falls processed Neihart ore, and the town became the undisputed hub of the local mining district.

Miners on payday flocked to the great mining camp to sample its saloons, play a game of cards, and visit the ladies in its several parlor houses. The bottom fell out of the silver market in 1893, but Neihart escaped the fate of most silver camps because its mines continued to sporadically operate. Total production of the Neihart mines up to 1900 included 4,008,000 ounces of silver and 10,000,000 pounds of lead. The 1940s saw the last burst of activity when silver prices briefly increased. By 1949, most mines closed permanently.

The mines and mills, whose remnants still dot the hillsides, helped lay the cornerstones of Montana’s economy. Six miles of underground tunnels lie beneath the hills surrounding Neihart. But today, above ground, it is tourism that boosts the local economy.

|

| Postcard courtesy Penny Postcards from Montana |

|

| The remains of mining in Neihart |

Monday, July 22, 2013

Frank Lloyd Wright in Montana

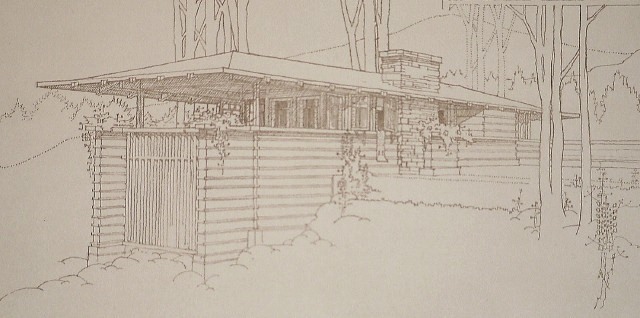

In 1991, the American Institute of Architects honored Frank Lloyd Wright as the Greatest American Architect of All Time. His theory of organic architecture held that structures should be in harmony with humanity and the human environment. When he died in 1959, he had designed over five hundred homes and structures in thirty-six states and Japan, Canada, and England. Some four hundred remain today. Montana claims several examples of his work, including one project from 1908 when Wright’s career was just beginning to take off and another dating to the very end of his long architectural practice. The Como Orchards Colony, also known as the University Heights subdivision, in the Bitterroot Valley near Darby was an experimental planned community. Wright came to Montana in 1908 to research the site and designed the Como Orchards as a summer refuge for university professors.

A lodge and thirteen cottages were completed. One small cottage, a one-room cabin, and a tree-lined drive are all that remain today of Wright’s experiment. It was an innovative idea and a very early use of the prairie style that made Wright famous.

He also designed the Bitterroot Inn at Stevensville, but it burned to the ground in the 1920s. The Lockridge Medical Clinic in Whitefish, built in 1961 1959, was one of Wright’s last designs. Dr. T. L. Lockridge insisted on the building’s construction even though his partners did not think it suitable as a medical clinic. For one thing, its hallways were too narrow for wheelchair access. When Lockridge died in 1964 1963, his two partners moved elsewhere, and Mrs. Lockridge sold the building. Now a law office, it is a surprising landmark in the middle of downtown Whitefish.

Update: Thanks to Ann Lockridge Christman for correcting the dates in the last paragraph.

|

| The Como Orchards Colony lodge. Courtesy Treadway/Toomey Galleries |

|

| A Como Orchards Colony cabin. Courtesy ArchiTech Gallery. |

|

| The Lockridge Medical Clinic in Whitefish |

Labels:

architecture,

Darby,

Montana,

Stevensville,

Whitefish

Friday, July 19, 2013

Friday Photo: Fly Fishing

|

| Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, PAc 98-12.12 |

P.S. Remember these anglers?

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

Refrigerators

Montana housewives read the newspapers and kept up with modern trends. They looked forward to modernizing their kitchens with the latest conveniences. One of the most important advances was home refrigerators, first introduced in 1911. In 1918, Kelvinator introduced the first refrigerator with an automatic control. The first freezer units were on the market in the 1920s, and in 1922 one model with a water-cooled compressor, two ice-cube trays and nine cubic feet of space cost a whopping $714! Consumers had two hundred different models to choose from. These early electric models usually had a separate compressor driven by belts attached to motors installed in the basement or adjoining room.

During the holiday season of 1930, the new Kelvinator refrigerator included the Kelvinator tray, making preparation of frozen desserts easy. Recipes for frozen delights were all the rage. Particularly popular were cranberry ice, frozen plum pudding, and a frozen Christmas salad made with cream cheese, green peppers, chopped pimiento, lemon juice, and whipped cream.

Invention of the flexible ice-cube tray was still to come in 1932, and mass production of refrigerators didn't get started until after World War II.

|

| Fred Mizen, artist, "For the Hostess," Kelvinator Refrigerators, 1920s Courtesy saltycotton, via Flickr |

|

| This 1933 booklet was produced by by the Kelvin Kitchen section of Kelvinator Sales Corporation of Detroit, Michigan. Courtesy Kristen N. Keegan, History Live |

Monday, July 15, 2013

Dedicating the Going-to-the-Sun Road

Glenn Montgomery cooked for several of the crews that built Going-to-the-Sun Road and was head cook for West Glacier Park. But never in his career did he feed more people than on July 15, 1933, the day Going-to-the-Sun Road was dedicated. Park officials expected to serve lunch to twenty-five hundred people before the opening ceremony. The day before, Montgomery gathered his groceries, including 500 pounds of red beans, 125 pounds of hamburger, 36 gallons of tomatoes, 100 pounds of onions, and 15 pounds of chili powder. The brew bubbled on four woodstoves in nine copper-bottomed washtubs until midnight. Crews transported the first batch of hot chili up to Logan Pass and transferred it to waiting cook fires to keep it hot. Meanwhile back at headquarters, Montgomery prepared a second batch that cooked the rest of the night. Nineteen-year-old Ernest Johnson, who worked on the road’s construction at forty cents an hour, stayed up all night helping to stir the chili.

The morning dawned sunny and clear, drawing four thousand people to the festivities on Logan Pass. The chili stretched thin, but with additional hot dogs and coffee, everyone got something to eat. Johnson later said that he slept through the event, but helped clean up the mess. He never saw so many paper plates in all his life.

From Montana Moments: History on the Go

|

| At the dedication of Going-to-the Sun Road Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, 956-617 |

From Montana Moments: History on the Go

Labels:

food,

Glacier National Park,

photo

Friday, July 12, 2013

Friday Photo: The Bookmobile Comes to Fairfield

|

| Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, PAc 89-38 F5 |

Location:

Fairfield, Montana

Wednesday, July 10, 2013

B Street Brothels, Livingston

Every Montana town had its red light district, and remnants of these places survive in many communities. Buildings and houses have usually been adapted for other uses and their histories forgotten. One exception is the railroad town of Livingston’s quaint little B Street Historic District, once a thriving neighborhood that catered to railroaders. At one time there were nine houses. Five of them on the street’s east side survive. Built between 1896 and 1904, these unusual little cottages feature gables and porches that resemble those of larger homes. Identical in composition, they have front porches with thin columns and small attic windows. Each had two separate front doors, a brick chimney on each half, and three small rooms, called “cribs,” on each side.

There was also a small waiting area just inside each front door. Mid-range brothels like these often housed cribs enclosed within the house and were built without kitchens and bathrooms. These types of establishments were meant to look like real homes, but they had no conveniences. They gave patrons—in Livingston, mostly traveling railroad men—the impression of a “home away from home,” but in reality offered few creature comforts. Livingston’s B Street Historic District operated until it closed in 1948. Four of the cottages, resembling tiny wooden temples, retain good architectural integrity. Homeowners in one of the houses removed the partitions and added a loft. Wanting others to appreciate their home’s interesting history, they also preserved a patch in the floor, added during the historic period, to cover a hole worn by an iron bedstead.

P.S. Remember this brothel-turned-courthouse?

There was also a small waiting area just inside each front door. Mid-range brothels like these often housed cribs enclosed within the house and were built without kitchens and bathrooms. These types of establishments were meant to look like real homes, but they had no conveniences. They gave patrons—in Livingston, mostly traveling railroad men—the impression of a “home away from home,” but in reality offered few creature comforts. Livingston’s B Street Historic District operated until it closed in 1948. Four of the cottages, resembling tiny wooden temples, retain good architectural integrity. Homeowners in one of the houses removed the partitions and added a loft. Wanting others to appreciate their home’s interesting history, they also preserved a patch in the floor, added during the historic period, to cover a hole worn by an iron bedstead.

P.S. Remember this brothel-turned-courthouse?

Monday, July 8, 2013

Central School: Most Prized of the Lot

Red bricks mark two time capsules that lie beneath the sidewalk along Warren Street in front of Central School. Children ceremoniously placed them there a few years ago, confident that the school would still stand in 2055 for other generations of children to open. Central’s alumni brick project, begun a decade ago, illustrates how this historic school on its prominent vantage point is not just a building. The school itself is a time capsule of the memories of generations and the living heart of the Helena community. Bricks along the Warren Street sidewalk, bordered by small handprints, complement the time capsules and commemorate alumni and teachers from 1913 to the present time. Central’s importance, however, goes back much farther than 1913.

Officials broke ground for the first Central School, originally called the Helena Graded School, on July 29, 1875. City fathers put a great deal of thought into its location. Helena was still a rough-and-tumble gold camp, but its inclusion along the projected Northern Pacific Railroad’s route gave it new prestige. That fact, coupled with the locating of a federal assay office—one of only five in the nation—at Helena, helped wrest its designation as territorial capital away from Virginia City. In preparation for this honor, city fathers planned the best school in the territory on the most visible site. The location was so critical and the site they selected so perfect that it was worth the effort to relocate the city’s cemetery, established on that prominent ridge in 1865. Helena Graded School opened in January 1876, built with 350,000 Kessler bricks. It was the first school in Montana Territory with separate classrooms for the various grades, a high school curriculum, and a kindergarten. By 1889, Central School was perhaps not the most architecturally pleasing, but of Helena’s seven public schools it was the “oldest and most familiar structure in the city and….the most prized of the lot."

The current Central School, designed by George Carsley, opened in 1915, built just behind the older school. Sydney Silverman Lindauer was among its first students. Like many other native-born Helenans, she moved away but never forgot her roots. Born in 1909, Sydney carried memories of Helena with her all of her ninety-six years. As she embarked upon her life’s final chapter, she shared her fondest thoughts. Foremost among them were cherished memories of Central School. During her attendance, both old and new schools stood together for a time until the old Central was razed in 1921 and the two symmetrical wings were added to the new building.

At Central School, Sydney found memorable teachers and lifelong friends including classmate Marjorie Stewart, daughter of Governor Samuel Stewart. The Stewarts were the first executive family to occupy the Original Governor’s Mansion. Sydney credited Central with the foundation that molded her into a celebrated columnist. She wrote for the Red Bluff, California, Daily News for forty-five years. Sydney recalled never wanting to miss a day of school. She walked to Central even when the snow was higher than the top of her head. Trustees at the Lewis and Clark County jail shoveled paths for the students. Sydney and her friends somberly watched the guards sit on piles of shoveled snow with guns drawn. And she never forgot the Central cheer that went something like “Strawberry shortcake, huckleberry pie, V-I-C-T-O-R-Y.” Shortly before she passed away in 2005, Sydney asked for a Central brick with her name and the date “1919.” She did not live to see her name set in the sidewalk, but she knew it was there along with the names of many other alumni she had known.

The present Central School will reach the century mark in 2015, when the first of the two time capsules is slated for opening. It would be the first existing Helena school to reach such a milestone. Central’s continued presence on its prominent ridge is more than a school board issue. It is a community concern. Not only does Central School maintain a place of honor as a historic cornerstone of Montana’s public school system, it is the ambassador for all Helena’s historic schools. What happens to it sets a precedent. And its fate affects not only the immediate Central neighborhood, but also the community and those who travel here to experience Helena’s historic landscapes.

Support the preservation of this community icon at www.savehelenaschools.com, and if you have a Central School memory, please share it on the Montana Historical Society's Facebook page.

Officials broke ground for the first Central School, originally called the Helena Graded School, on July 29, 1875. City fathers put a great deal of thought into its location. Helena was still a rough-and-tumble gold camp, but its inclusion along the projected Northern Pacific Railroad’s route gave it new prestige. That fact, coupled with the locating of a federal assay office—one of only five in the nation—at Helena, helped wrest its designation as territorial capital away from Virginia City. In preparation for this honor, city fathers planned the best school in the territory on the most visible site. The location was so critical and the site they selected so perfect that it was worth the effort to relocate the city’s cemetery, established on that prominent ridge in 1865. Helena Graded School opened in January 1876, built with 350,000 Kessler bricks. It was the first school in Montana Territory with separate classrooms for the various grades, a high school curriculum, and a kindergarten. By 1889, Central School was perhaps not the most architecturally pleasing, but of Helena’s seven public schools it was the “oldest and most familiar structure in the city and….the most prized of the lot."

|

| Central School students pose behind the school circa 1910. Photo by Edward Reinig Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, PAc 74-104.292 GP |

The present Central School will reach the century mark in 2015, when the first of the two time capsules is slated for opening. It would be the first existing Helena school to reach such a milestone. Central’s continued presence on its prominent ridge is more than a school board issue. It is a community concern. Not only does Central School maintain a place of honor as a historic cornerstone of Montana’s public school system, it is the ambassador for all Helena’s historic schools. What happens to it sets a precedent. And its fate affects not only the immediate Central neighborhood, but also the community and those who travel here to experience Helena’s historic landscapes.

Support the preservation of this community icon at www.savehelenaschools.com, and if you have a Central School memory, please share it on the Montana Historical Society's Facebook page.

Friday, July 5, 2013

Friday Photo: Mule Team

|

| Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, 957-871 |

Labels:

Anaconda,

Fourth of July,

holidays,

Montana,

photo

Thursday, July 4, 2013

A Second Perspective on the Fourth of July in Alder Gulch, 1865

While yesterday's post presents one view, here is another recollection of the same celebration. In her reminiscence, Girl from the Gulches, Mary Ronan recalls the Fourth of July in Virginia City, 1865. The Civil War was finally over, and hostilities that pervaded even the most remote mining camps in Montana Territory had calmed and lessened. Mary remembers that it was “a day atingle with motion, color, and music.” People thronged on the board sidewalks and footpaths, and horses and wagons crowded the street, lining up to view the parade. Mary was proud to ride with thirty-six other little girls all dressed in white on a dead-ax wagon—that is, a wagon with no springs—festively decorated with evergreens and bunting. In the center of the “float,” if one could call it that, the tallest and fairest of the girls stood motionless, dressed in a Grecian tunic with a knotted cord at her waist. Her long blond hair flowing behind her, she represented Columbia, the personification of the United States. The other little girls sat arranged in groups at Columbia’s feet representing the States of the Union. Each wore a blue scarf fashioned as a sash across her chest. A letter on each sash identified the state represented.

For Mary, the memory was bittersweet. Her letter stood for Missouri, a state in which she had lived. But she wanted to represent Kentucky, the state of her birth. Some other little girl, however, had already taken the K. The other bitter pill was that Mary worried self-consciously about her appearance. She had suffered all night with her extremely long hair painfully done up in rags—one method girls back then employed to curl their hair. But the result was less than desirable. It left her hair much too bushy and kinky!

|

| Mary Ronan at the time of her marriage, 1873. Courtesy Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library, University of Montana |

Labels:

children,

Civil War,

Fourth of July,

Girl from the Gulches,

holidays,

Montana,

Virginia City,

women

Wednesday, July 3, 2013

The Fourth of July in Alder Gulch, 1865

Much has been made of the lines of allegiance drawn in Montana over the Civil War. Mary “Mollie” Sheehan Ronan danced for joy with her southern friends upon Lincoln’s assassination, and Harriett Sanders wrote of celebrations Southern women planned over Lincoln’s death. But Julia Gormley tells a different tale about Civil War loyalties in Alder Gulch. When word reached the gold camps, about ten days after Lincoln’s assassination, stores closed and flags flew at half staff. There were appropriate speeches and a midnight procession with the band playing a march for the dead. Then, on the Fourth of July that year, with the Civil War over, Julia later recalled that Judge Lott asked her to sing at the Independence Day festivities. She declined, but suggested he ask the Forbes sisters, who were good singers. When Judge Lott asked them, they were indignant to have been asked to sing at such a celebration. They were Southerners from Missouri who had lost their home and suffered greatly at the hands of Union soldiers. Judge Lott retuned to Julia and asked her why she had sent him into the rebel camp unprotected. Julia replied that he should not complain since he was not taken captive. Julia confessed that they had a good laugh over the situation. And later, the Forbes sisters did too. Julia goes on to say that she took her children to see the Independence Day parade in Virginia City. “It was really a very fine thing,” she wrote, “to see the good feeling between the Southern and Northern people way out there and strangers to each other join so heartily together on that 4th of ’65.”

|

| Harper's Weekly published this illustration, "Peace," on July 4, 1865. |

Labels:

Civil War,

Fourth of July,

holidays,

Montana,

Virginia City,

women

Monday, July 1, 2013

Reeder’s Bricks

Louis Reeder was a Pennsylvania brick and stone mason who came to Helena in 1867 not to mine, but to build. He knew that the community would need fireproof buildings, and that is how he intended to make his fortune. Soon he had a number of contracts, and he saved his money and invested in property. One of these properties was a collection of buildings that spread up a narrow alley. Reeder added to them. Eventually, thirty-two tiny one-room apartments offered miners better living conditions than the log cabins they were used to.

The distinctive red bricks of Reeder’s Alley have been the subject of a persistent myth linking them to artist Charlie Russell. Russell’s family owned the Parker-Russell Mining and Manufacturing Company in St. Louis, Missouri, a leading maker of industrial fire brick. Rumor has it that some of the Reeder’s Alley bricks came by ox team from the Russell Company. Reeder’s Alley, however, contains no fire brick, and there was never a need to import building brick to Helena. By 1866, Nick Kessler was making both building and fire bricks. Industrial fire bricks were used, for example, in lining the lime kilns at the south end of West Main Street. Inspection of the kilns reveals a variety of imported fire brick from Chicago, St. Louis and elsewhere, but there are no Parker-Russell bricks in the kilns. There does, however, seem to be some truth to the rumor that Parker-Russell bricks came to Helena. The homeowner of the May Butler House at the end of South Benton Avenue discovered a large stash of unused bricks buried in the yard. These bear the surprising stamp of the Parker-Russell Manufacturing Company.

P.S. Remember this Reeder's Alley prank?

|

| Reader's Alley today |

P.S. Remember this Reeder's Alley prank?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)