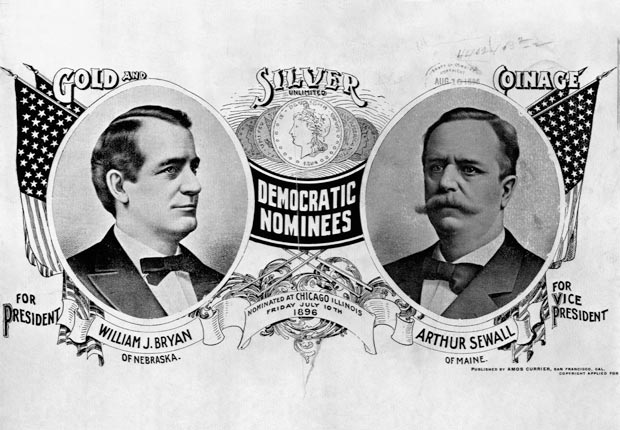

Did your candidate win yesterday's election? Here's a look back at the 1896 presidential election, which disappointed four out of five Montana voters.

The Populist Party was one of the most significant third political parties in the history of the United States. In the 1890s, Populism grew among Midwestern and southern farmers who believed that the free coinage of silver would cause inflation, which would raise farm prices and thus benefit the depressed agricultural economy. The populist platform also advocated nationalization of railroads, a graduated income tax, and more direct citizen participation in government. In Montana, where silver mining was an important industry, miners backed the Populist Party, especially after the collapse of the silver market in 1893. William Jennings Bryan’s “

Cross of Gold” speech countered the Republicans’ backing of the gold standard.

|

| A button from William Jennings Bryan's 1896 campaign |

Montana elected three Populists to the state senate and thirteen to the house. Populism in Montana reached its peak in the presidential election of 1896 when Populists joined Democrats to back William Jennings Bryan for president. Bryan was an advocate of free silver coinage and spokesman for the cause of the poor man. Marcus Daly reportedly gave $50,000 to Bryan’s campaign and was its largest contributor. Butte and Anaconda especially embraced Bryan as a champion of the working man, the antithesis of wealth and power, and thus one of their own.

Bryan carried Montana four to one in the election, but he lost to William McKinley. On the heels of his defeat, Bryan visited Montana the following August of 1897. Butte is famous for its hospitality, but Bryan received the greatest welcome Butte has ever bestowed on any visitor, and a poem, “

When Bryan Came to Butte,” received national press. By 1906, Populism had faded and its free silver platform failed, but it left an important legacy. This included the eight-hour workday, direct election of senators by the people, the process of referendum and initiative, and a solid foundation for the Progressive era that followed.

P.S. I'll be signing books at the

Montana Historical Society tomorrow (November 8) from 11:00 until 1:00. Plus there will be tea and cookies. Hope to see you there!