A canyon twelve miles west of Missoula bears the name of a colorful character time has forgotten. He helped build the Mullan Road and planted an orchard in Missoula County. Cornelius O’Keefe introduced the first farming equipment in Montana—thresher, reaper, and mower—and made a small fortune freighting his crops to local mining camps. Perhaps because he came from Ireland, his best crop was potatoes, which he sold by the wagonload to the potato-starved residents of Bannack and Virginia City. O’Keefe once had a lawsuit brought against him, the very first in Montana. When O’Keefe told Judge Henry Brooks he planned to represent himself, the judge took out a deck of cards, and shuffled them. “These are my credentials,” said the judge. “What are yours?” he asked O’Keefe. O’Keefe answered, “These are my credentials,” and punched the judge right between he eyes. The judge didn’t argue. O’Keefe was always known as Baron O’Keefe. Elected twice to the territorial legislature, he acquired the title when he had to sign the official roster. Instead of noting his occupation as “farmer,” this picturesque Irish gentleman registered as “land baron,” and Baron O’Keefe he was from that time on.

From Montana Moments: History on the Go

Monday, April 30, 2012

Friday, April 27, 2012

Friday Photo: Spring Roundup

Happy Friday! Here's an iconic photo of a highly romanticized chapter in Montana history.

Photographer L. A. Huffman snapped this photo during the spring roundup near Miles City, probably in the 1890s. He called it "Foreman Telling Off the Men for the Circle," describing the routine to start the day's work.

P.S. Remember this depiction of cowboy life?

|

| Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, 981-460 |

P.S. Remember this depiction of cowboy life?

Wednesday, April 25, 2012

Shep

In the summer of 1936, a sheepherder became ill and was brought to the hospital in Fort Benton. A dog followed his flock of sheep into town and hung around the hospital where a kindly nun fed him. The herder died, and his relatives asked that his body be sent back East. The undertaker put the casket on the train, and the engine pulled away. The dog followed along the tracks until the train sped away, beginning a five-and-a-half year vigil. Day after day, the dog—named Shep by locals—met every passenger train, eying each person who got off. Neither heat nor rain nor snow prevented Shep from meeting those trains. Irene Schanche Bowker recalls that her father, depot agent Tony Schanche, coaxed the dog into the depot from the cold station platform. After gaining his trust, Schanche taught him tricks. Shep’s fame spread, and people came to photograph him, try to make friends, and possibly adopt him. But Shep was a one-man dog. The bond he had formed with the herder was simply the most important thing to him. Although railroad employees gave Shep food and shelter, that was all he wanted, except his master’s return. Time took its toll. On January 12, 1942, stiff-legged and deaf, Shep failed to hear the whistle as the 10:17 approached the depot that cold winter morning. Witnesses said he turned to look when the engine was almost upon him, moved to get out of the way, and slipped on the icy rails. His long vigil ended. Two days later, Shep had a grand funeral. Boy Scouts played taps, and a local minister read a moving eulogy on man’s best friend. Loving citizens laid Shep to rest on the bluff overlooking the station where his long wait had come to a sad end.

|

| From Roadtripamerica.com |

Labels:

dogs,

Fort Benton

Location:

Fort Benton, Montana

Monday, April 23, 2012

William A. Clark

Historian Joseph Kinsey Howard said that a dollar never got away from Copper King William A. Clark except to come back stuck to another. Clark was intelligent, ambitious, and obsessed with his own vanity. Butte was his stronghold. Clark gave his miners there a magnificent park and an eight-hour workday.

Clark spared no expense on his 1880s mansion in Butte. The thirty-plus rooms had electric as well as incandescent and gas lighting, and a fifteen-hundred-gallon tank on the third floor supplied the household with running water. The home’s beveled French plate glass windows with blinds of hardwood that folded into pockets and frescoed ceilings had no equal in the West.

Montana saw little of Clark after 1900, when he served an undistinguished six years in the U.S. Senate. Clark endowed a library and built a theater at the prison in Deer Lodge—the first prison theater in the United States—to thank the warden for the use of convict labor on his ranches and in his mines. But Clark took his vast fortune elsewhere. His wealth endowed the University of Virginia’s law school, the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, and the University of California’s library. None of it ever came back to Montana.

From Montana Moments: History on the Go

P.S. Check out this menu for a banquet given by Clark.

|

| Clark with his daughters, Andrée (left) and Huguette, c. 1917. Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives |

|

| Today, Clark's mansion is a bed and breakfast. |

From Montana Moments: History on the Go

P.S. Check out this menu for a banquet given by Clark.

Labels:

Butte,

copper kings,

Deer Lodge,

Montana Moments,

theaters

Friday, April 20, 2012

Friday Photo: Electricity Comes to Libby

Aren't you glad that safety standards have come a long way since then?

The caption in the lower corner reads: "Stringing the first electric light wires in Libby Mont July 1911." Photographer unknown.

|

| From Montana Views. Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, PAc 97-14.8 |

Location:

Libby, Montana

Wednesday, April 18, 2012

Paris Gibson Junior High Blows Up

Central High School in Great Falls opened in 1896. It took a creative community three years to build it. To prepare the uneven ground, sheepherders drove a herd of sheep around the site one hundred times trampling down the dirt. Huge logs floated to Great Falls on the Missouri River were shaved flat on all four sides and became the beams for the floor supports, attic framework, and stairways. The massive blocks of sandstone that form the walls came from a quarry near Helena and rest on a foundation sixteen feet thick in some places.

|

| From National Register of Historic Places listing |

Great Falls judged Central the best school west of the Mississippi. Its crowning feature, a huge Norman-style clock tower, arose out of the central part of the building. However, it was so heavy that it finally became unsafe, and the school took it down in 1916. According to locals, the custodian and his family lived in the school’s attic. A sink with running water and wallpaper on the walls made the apartment quite homey. The daughter, however, was embarrassed to live in the school’s attic. She would leave home early in the morning, walk away from the building before the other students began to arrive, and then walk to school with her classmates. In 1913, a brick annex with an auditorium and gymnasium doubled the size of the school. From 1930 to the 1970s, the school served as Paris Gibson Junior High. In 1977, it became the Paris Gibson Square Museum of Art. But just before this adaptive reuse, movie makers blew up the annex in a controlled demolition for a scene in Telefon, starring Charles Bronson and Lee Remick.

Labels:

architecture,

children,

Great Falls,

schools

Monday, April 16, 2012

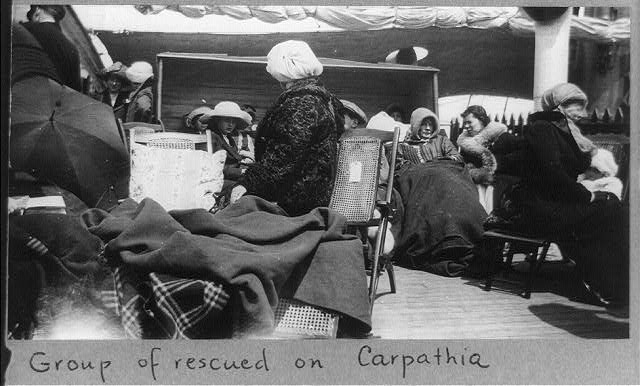

Titanic Memory

One hundred years ago yesterday, the Titanic sank...

Twenty-year-old Mary Lawrence left Austrian Hungary, employed as a maid to a physician’s family en route to America. Mary seldom spoke about her terrible ordeal aboard the ill-fated Titanic, but in 1939, she did describe her experience to a news reporter. She recalled the utter horror of that night, April 15, 1912. First she heard a terrible crunching sound, then people running, screaming, crying, and shoving and pushing. She saw many fall overboard, and she saw her employer—the doctor—and his wife and their three children—all go over the side of the huge ship and into the water. She jumped from the sinking ship into a boat, suffering a severe and permanent injury to her leg as she landed. All around her people were drowning in the ice-cold water. She recalled crowding into the lifeboat, and several people froze to death during the five hours before help came.

She could not remember the rescue, but once she arrived at New York City, Mary recalled wandering the streets aimlessly, dazed, homeless, injured, and unable to speak English. After several weeks, she finally met someone from her native homeland who helped her find work on a farm. Several months later she learned of an uncle in Montana. Mary traveled to Dillon and stayed with her uncle there for several years. In 1915 she married Jacob Skender, a miner and smelter worker. The Skenders settled in the Butte neighborhood of Meaderville where they raised six children, but Mary could never put aside that terrible experience. There were more than 2,200 people on the Titanic’s maiden voyage. Of those, Mary Lawrence Skender was one of 705 survivors.

Twenty-year-old Mary Lawrence left Austrian Hungary, employed as a maid to a physician’s family en route to America. Mary seldom spoke about her terrible ordeal aboard the ill-fated Titanic, but in 1939, she did describe her experience to a news reporter. She recalled the utter horror of that night, April 15, 1912. First she heard a terrible crunching sound, then people running, screaming, crying, and shoving and pushing. She saw many fall overboard, and she saw her employer—the doctor—and his wife and their three children—all go over the side of the huge ship and into the water. She jumped from the sinking ship into a boat, suffering a severe and permanent injury to her leg as she landed. All around her people were drowning in the ice-cold water. She recalled crowding into the lifeboat, and several people froze to death during the five hours before help came.

|

| Survivors of the Titanic on board the rescue ship Carpathia. Library of Congress |

Friday, April 13, 2012

Cattle Drives

Cattle drives might be a thing of the past, but supposedly there are still three cows to every person in Montana. Some still practice cowboy skills. And for greenhorns like myself, there are learning opportunities if you know where to look. I will be honing my limited skills at a cow horse cutting clinic this weekend!

Jesuit missionaries in the Bitterroot Valley and some of the early traders, including Johnny Grant in the Deer Lodge Valley, drove the first shorthorn cattle herds to Montana long before the gold rushes of the 1860s. James Liberty Fisk noted cattle grazing in the Prickly Pear Valley in 1863. But it was Nelson Story who drove the first herd of Texas longhorns into Montana in 1866 in a legendary drive fraught with danger. Story invested a good portion of his $30,000 fortune in gold dust on this venture. He purchased a thousand head of cattle at ten dollars a head and hired twenty-five of the most experienced, toughest cowboys. Armed with colt revolvers, these men were full of courage and grit driving the huge herd through dangerous territory in Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming. At Fort Laramie, Story armed his men with new Remington breech-loading rifles for protection along the dangerous Bozeman Trail. It was needed, too, as Sioux attacked the group, wounded several drovers, stole some cattle, and stampeded the herd. At dusk, drovers rode into the Sioux camp and, in a daring raid, recovered their stolen cattle. Sioux again attacked several times more. At Fort Reno, the army ordered Story to halt, promising that Indians would kill them all. But defying orders, Story and his men drove the cattle by night, and in December 1866, after nine months, they arrived in the Gallatin Valley. Livestock and open range ranching quickly became a huge industry, and skilled cowboys were essential. Roundups gathering the herds for spring branding and fall shipping were the pulse of the cowboy life. As the Northern Pacific steamed across America’s last frontier in 1883, overland cattle drives, once a necessity to move livestock to market, became a thing of the past. Barbed wire encroached and the open range and the vast herds of yesteryear disappeared. Cowboys and their way of life passed into legend.

|

| B.B. Sheffield cattle roundup in coal creek badlands, Diamond W Ranch, Calabar, Montana, date unknown. Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, 981-624 |

Wednesday, April 11, 2012

Smoking Cure

Many Montanans have fond, and not so fond, childhood memories of Virginia City. Eileen Yeager, who grew up there in the 1890s, tells a story in the Madison County history Trails and Trials about games she and her sister Mary made up to amuse themselves. One was called “Bob and Bill.” This game involved gathering old chewed cigar butts from behind a certain barn. Each girl had a cigar box that she filled with the old stogies. They had made a sidewalk of scrap wood in the backyard, and beginning at opposite ends, they sauntered toward each other, dressed in their dad’s old hats. They met in the middle and took turns. Eileen would say, “Hello Bill.” Mary answered, “Hello, Bob.” They had a set dialogue, and after a bit, Eileen would say, “Would you like a cigar?” and open her cigar box. Each would take a stogie, light up, and saunter down the sidewalk puffing away. Then they would switch roles and do it again. One day, Mary must have forgotten and inhaled. She keeled right over, and Eileen ran into the house announcing dramatically, “Mama, Mary is dead!” Their mother rushed out to find Mary violently ill. She called the doctor who immediately asked Eileen, “What have you been smoking?” Eileen showed him the box of damp, chewed cigar butts. This time her mother keeled over. Eileen didn’t understand why her mother fainted, but the spanking made a lasting impression. Thus Eileen quit smoking at the age of six, and neither she nor Mary ever took it up again.

Labels:

children,

Virginia City

Location:

Virginia City, Montana

Monday, April 9, 2012

Legal Beer

Eight months before the official end of Prohibition, patrons at Walkers Bar in Butte raised glasses of beer in celebration. A sign read, “The only place in the United States that served Draught Beer over the bar April 8, 1933.” President Franklin Roosevelt gave the repeal of Prohibition top priority because traffic in illegal liquor fostered so much criminal activity. Roosevelt knew its repeal would take time. So when he took office in 1933, he signed the Cullen-Harrison Act legalizing beverages with an alcohol content of 3.2 percent. Twenty states, including Montana, legalized 3.2 beer. The law took effect on April 7, and within twenty-four hours, the nation consumed 1.5 million barrels of beer. Montana enjoyed its 3.2 beer until the Twenty-first Amendment repealing Prohibition took effect eight months later on December 5.

|

| Photo from Metals Sports Bar |

Although Montana was one of twenty states legalizing 3.2 beer, except for Walkers in Butte, beer didn’t magically appear in local Montana bars. While state beer licenses brought in seventy-three thousand dollars in the first two days, legal beer only trickled into the state. The first shipment of 3.2 Pabst left Milwaukee on April 7, the very same day it became legal. A new refrigerated warehouse at the Northern Pacific Railway yards in Helena waited to store it for distribution. But it was five days before Helena got its first taste of legal beer. With 1.5 million barrels of beer consumed nationwide in the first twenty-four hours after the signing of the Cullen-Harrison Act, Walkers could not have been the country’s only outlet. The question is: how did Walkers get its first legal 3.2 beer at a moment’s notice?

Labels:

bars,

Butte,

Prohibition

Location:

Butte, Montana

Friday, April 6, 2012

Ming Opera House/Consistory Shrine

In celebration of Easter...

Masons have been a dynamic force in Montana since early territorial days, playing key roles in events that shaped the state’s history. Helena Masons first came together in 1865 for the funeral of Dr. L. Rodney Pococke, for whom Rodney Street was named. The fraternal organization has since been closely intertwined with the Helena community. The Masons acquired the former Ming Opera House in 1912. Built by John Ming in 1880 and renowned throughout the Pacific Northwest, the theater followed a circular plan model after fashionable European opera houses. It featured thirty-two sets of elaborate scenery, seating for 900, gas lighting in the house, and state-of-the-art stage lighting which included twenty-six movable border lights. Rubber tubing delivered gas to the house and stage lights from a plant in the stone cellar. The Ming hosted such famous performers as Otis Skinner, Eddie Foy, Marie Dressler, and Katie Putnam. Patrons’ safety was not a consideration until 1887. John Ming renovated the opera house after 100 people literally roasted alive in an opera house fire in Exeter, England. Ming added ample exits and updated the gas lighting system.

In the early 1900s, the Ming hosted the first silent movies. In 1915, noted Helena architects George Carsley and C. S. Haire redesigned the building, transforming the theater into a more functional, modern auditorium. Under the Masons’ care, the original hand painted 1880s scenery remains in occasional use. For the past sixty-three years, the Scottish Rite of the Freemasons have performed an Easter Tableaux, reenacting scenes from the Last Supper to the Ascension. The free performance utilizes the historic 1880s scenery and is the only time the public can view these exquisite remnants of 1880s Helena. The landmark building at 15 North Jackson in Helena survives thanks to the Masons’ stewardship and continues to serve as a meeting place for members of all the Masonic orders.

|

| Ming Opera House, left, 1898. Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, 953-833 |

|

Location:

15 N Jackson St, Helena

Wednesday, April 4, 2012

Prison Escape

Warden Frank Conley at the Montana State Prison in Deer Lodge kept fearsome full-blooded hounds trained to track escapees. They were enclosed in a high fence inside the prison walls. In 1902, prisoner Thomas O’Brien foiled these hounds in a spectacular getaway. O’Brien, who claimed he was innocent of grand larceny, had served half of his five-year sentence. He was a trustworthy prisoner who had some freedom in his assigned job as stable boss of the large barn outside the prison walls. O’Brien claimed he had veterinary training, and so he obtained medicines for the animals. He had worked for two weeks conditioning George Tighe, the warden’s prize Thoroughbred racehorse. When the time was right, O’Brien obtained some opium, supposedly to treat one of the animals, and used it to put Warden Conley’s bloodhounds into a deep slumber. He then calmly saddled George and rode off toward the prison ranches. The guards assumed that he was on some legitimate errand. As the distance between them grew greater, O’Brien coaxed the horse into his fastest run and went the other way. The hounds were of no use. Officials later found the saddle and bridle hanging in a tree and George loose in a pasture. O’Brien was on the lam for eighteen days, then gave himself up. En route back to Deer Lodge, the prison escort treated O’Brien to breakfast and a cigar. Once back in prison, Warden Conley shook O’Brien’s hand and commended him for surrendering. Perhaps O’Brien really was innocent. Less than a year later, the governor pardoned him.

|

| Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives |

Labels:

Deer Lodge

Location:

Old Montana State Prison, Deer Lodge

Tuesday, April 3, 2012

Extra! Extra! The Story of Mary Ronan

I have exciting news, history buffs! As of this morning, you can download Girl from the Gulches: The Story of Mary Ronan as an eBook. (Update: Kindle users can get the book here.) Mary Ronan grew up in the early Montana gold camps. In 1865, her father moved the family from Virginia City to Helena. They settled into a cabin on Clore Street (now Park Avenue), just up the block from the Pioneer Cabin. In this excerpt from the book, Mary remembers going to school in Helena.

Professor Stone and his brother opened a private school in August 1867, on Academy Hill not far above the first little Catholic Church where the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart was later built. At one end of the long room Professor Stone taught the primary grades. We sat in prim rows on long, rough benches. This was the largest and most interesting school I had ever attended. Professor Stone began a Latin class and I was a member. This gave me a feeling of great importance; I felt I was standing on the edge of real intellectual achievement! Most stimulating was the lesson each day in Webster's school dictionary, with strange sounding words to spell and define. Before school closed each afternoon the older students would pronounce words; we would each in turn rise, repeat the word, spell it, and sit down. Sallie Davenport always spelled down the school. One day Professor Stone's brother was conducting this drill. It was Raleigh Wilkinson's turn. Raleigh was the son of E. S. Wilkinson, Peter Ronan's partner in the Rocky Mountain Gazette. He misspelled the word.

"Try it again, Raleigh," said Mr. Stone.

"I don't think I can spell it," Raleigh replied.

"Well, try it," insisted Mr. Stone.

"I told you I don't think I can spell it," growled Raleigh.

Mr. Stone, himself young, large, and athletic looking, flushed angrily and repeated his command. "Well, try it, I tell you." Raleigh repeated his refusal. For several times more command and refusal were bandied back and forth in rising crescendo until a tempestuous climax came in an exchange of blows. Suddenly up jumped all the big boys and precipitated a melee. We girls fled from the schoolhouse to our homes. This free-for-all fight was the occasion of much talk among the patrons of the school for many days.

Professor Stone encouraged dramatic reading. One of my boy schooolmates and I practiced a dialogue, without any coaching, which we gave at a public "entertainment" in the schoolroom. Our stage was the little platform where the teacher had his desk. I was a Roman matron encouraging her husband:

"Have the walls ear? I wish they had an tongues, too, to bear witness to my oath and tell it to all Rome."

"Would you destroy?" my opposite intoned.

Fervently I picked up my cue, "Were I a thunderbolt! Rome's ship is rotten! Has she not cast you out?" The applause thrilled me and fired my ambition to be an actress. Professor Stone added fuel to the flame by complimenting me warmly.

I learned the part of Lady Anne in Richard III. I practiced at home in the little sitting room before the mirror, trying a variety of interpretations from mincing to flamboyant. My stepmother, who often admonished me for my vanity, became now positively alarmed for the salvation of my soul and forbade me to go on with the practices or to present at school what was to have been my "big performance."

From Girl from the Gulches: The Story of Mary Ronan

Professor Stone and his brother opened a private school in August 1867, on Academy Hill not far above the first little Catholic Church where the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart was later built. At one end of the long room Professor Stone taught the primary grades. We sat in prim rows on long, rough benches. This was the largest and most interesting school I had ever attended. Professor Stone began a Latin class and I was a member. This gave me a feeling of great importance; I felt I was standing on the edge of real intellectual achievement! Most stimulating was the lesson each day in Webster's school dictionary, with strange sounding words to spell and define. Before school closed each afternoon the older students would pronounce words; we would each in turn rise, repeat the word, spell it, and sit down. Sallie Davenport always spelled down the school. One day Professor Stone's brother was conducting this drill. It was Raleigh Wilkinson's turn. Raleigh was the son of E. S. Wilkinson, Peter Ronan's partner in the Rocky Mountain Gazette. He misspelled the word.

"Try it again, Raleigh," said Mr. Stone.

"I don't think I can spell it," Raleigh replied.

"Well, try it," insisted Mr. Stone.

"I told you I don't think I can spell it," growled Raleigh.

Mr. Stone, himself young, large, and athletic looking, flushed angrily and repeated his command. "Well, try it, I tell you." Raleigh repeated his refusal. For several times more command and refusal were bandied back and forth in rising crescendo until a tempestuous climax came in an exchange of blows. Suddenly up jumped all the big boys and precipitated a melee. We girls fled from the schoolhouse to our homes. This free-for-all fight was the occasion of much talk among the patrons of the school for many days.

Professor Stone encouraged dramatic reading. One of my boy schooolmates and I practiced a dialogue, without any coaching, which we gave at a public "entertainment" in the schoolroom. Our stage was the little platform where the teacher had his desk. I was a Roman matron encouraging her husband:

"Have the walls ear? I wish they had an tongues, too, to bear witness to my oath and tell it to all Rome."

"Would you destroy?" my opposite intoned.

Fervently I picked up my cue, "Were I a thunderbolt! Rome's ship is rotten! Has she not cast you out?" The applause thrilled me and fired my ambition to be an actress. Professor Stone added fuel to the flame by complimenting me warmly.

I learned the part of Lady Anne in Richard III. I practiced at home in the little sitting room before the mirror, trying a variety of interpretations from mincing to flamboyant. My stepmother, who often admonished me for my vanity, became now positively alarmed for the salvation of my soul and forbade me to go on with the practices or to present at school what was to have been my "big performance."

From Girl from the Gulches: The Story of Mary Ronan

Labels:

books,

children,

Girl from the Gulches,

Helena

Monday, April 2, 2012

Japanese Balloons

Historian Jon Axline tells a story about Oscar Hill and his son, who in 1944 were cutting firewood seventeen miles southwest of Kalispell. They found a strange parachute-like object with Japanese writing and a rising sun symbol stenciled on it. Sheriff Duncan McCarthy took the object to a Kalispell garage. Rumors flew and soon five hundred people crowded into the garage to take a look. It turned out to be a Japanese balloon rigged to carry a bomb. It was the beginning of an aerial attack on the United States by Imperial Japan as World War II wound down. In November of 1944, the Japanese began launching hydrogen-filled paper balloons believing the jet stream would carry them to North America. The attached incendiary and anti-personnel bombs would start forest fires and kill civilians. The Japanese also intended the balloon bombs as psychological weapons, designed to cause confusion and spread panic. The Japanese called them Fu-Go, “Windship Weapons.” They were the first intercontinental weapons, a low tech predecessor to the ballistic missiles of the late twentieth century.

By April 1945, the Japanese launched over nine thousand balloons. Only 277 reached the United States and Canada. Only one caused injuries, killing five Oregon picnickers when they inadvertently detonated one of the bombs. The project was a failure. A voluntary news blackout in the United States kept the Japanese from discovering if the balloons landed. At least thirty-two balloon bombs reached Montana between 1944 and 1945. A hiker discovered the last one hanging from a tree southwest of Basin in 1947. Axline points out that balloon bombs in Montana proved that the state was not as isolated and free from world events as the public thought.

Update: Here's a better photo of FBI agents examining the bomb. This one is an illustration in my new book, More Montana Moments.

|

| Army Intelligence Captain W. Boyce Stanard (left) watches as FBI special agent W. G. Banister examines the balloon that fell in Kalispell. Army Air Force Major J. E. Bolgiano is holding the balloon's pressure relief valve. Photo from Project 1947. |

Update: Here's a better photo of FBI agents examining the bomb. This one is an illustration in my new book, More Montana Moments.

|

| Donald D. Cook, photographer, Montana Historical Society Photograph Archives, PAc 93-1 |

Location:

Kalispell, Montana

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)